An Oral History of Hardcore Punk

(unpublished article, ca. 1995)

(Note: I conducted these interviews and more for a magazine story that never ran. What follows is a rough, incomplete edit of the piece. I held on to the tapes, and will be adding in interviews I did with SST producer Spot, Black Flag bassist Kira Roessler, Meat Puppets drummer Derrick Bostrom, Jody Foster's Army's Brian Bannon, plus more from Minuteman Mike Watt and the Big Boys' Tim Kerr.)

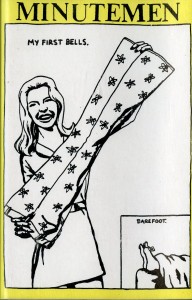

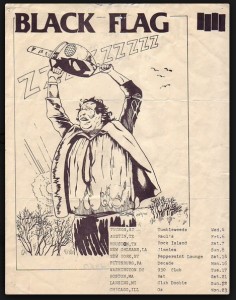

Mike Watt, the Minutemen: A lot of the revisionist writing about the old days of punk rock really plays up the British thing. All those major label bands like the Jam and the Clash. People don't really talk about SST Records and Black Flag actually building that club circuit that everybody uses now. In England, punk did get really big really fast in the seventies, and a lot of them bands got signed. Here it stayed really small, became kind of a fringe thing, so the only people involved were really dedicated to it. They created this fanzine culture, these little labels. But we would tour in those old days, and you would call the bands from each of the towns, and they would help you out and get things going. We were more like an old vaudeville thing: "Hey, let's take this music out. These Hollywood people won't let us play, we'll play over here, we'll go to Orange County, let's get to another town.' And the scenes in Shreveport or Boise would be so small that Black Flag would be their only punk show all year. Too bad Kurt ain't around because he could tell you this. I guess he's responsible for alternative or something, but if you talk to him, he grew up on the Germs and Black Flag, and waiting for that gig every summer.

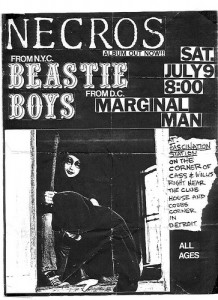

Andy Wendler, Necros: The real beauty of early hardcore was that this whole network of places to stay and people booking shows and distributing records just sprung up. It's really strange that a whole genre of music happened in almost every city in the country simultaneously. In Detroit, hardcore hit us with the first Black Flag EP, and then two weeks after it came out, we really started networking via Flipside magazine and seeing that there was a newer version of punk going on everywhere. And hardcore felt more like our music.

Al Barile, SS Decontrol: I was a typical suburban kid--I lived thirty minutes outside of Boston, and grew up on Van Halen and AC/DC. When I saw Black Flag, I thought "This is like AC/DC, but this is better.' And then I got together with a bunch of people and we all hopped in my van and went down to New York to see the Bad Brains. They were playing in a loft, and people just stood there and did nothing. New York and Boston were full of punkers hanging onto that 1979 Sex Pistols thing, people with spiky hair and leather jackets, drunk out of their minds and doing punk rock as a cool fashion thing. And we weren't into playing that role. The Bad Brains played and it was like the room was exploding. They were the band that defied any live experience I'd ever had. It was charged.

Darryl Jennifer, bassist, Bad Brains: We were four brothers in the DC projects who were into rock and jazz. We heard punk rock, and we thought we could do this and get some juice, maybe bring a little Return to Forever flavor to punk. All I know is that after we played a show, we would have enough money to go to IHOP. Personally, I was more into walking around clubs and setting tablecloths on fire.

Gregg Turner, Angry Samoans: There was a strange psychic metamorphosis going on in the summer of 1980 in Los Angeles. A certain angst and hostility had just blossomed. All the sudden, middle class white thirteen year olds were being given an opportunity to say "Hey we're unhappy and this is our way of expressing it and we can do it here.' That's sort of what it was all about. When the Angry Samoans played, there was this eruption that was almost as frightening as it was energizing. You had to wonder if the monster could turn on you at any minute.

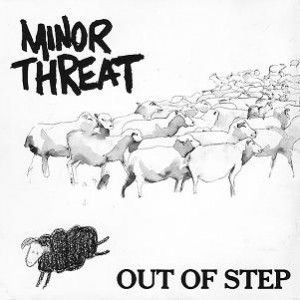

Lyle Preslar, guitar, Minor Threat: Hardcore music, stylistically, was marginal. An REO Speedwagon fan wouldn't like Black Flag. Black Flag looked like they'd been sleeping on the beach all night. But I thought that was great.

Raymond Pettibon, resident artist, SST records: I used to hang out at The Church in Hermosa Beach. Various members of Black Flag lived there, and it was originally the place where Greg Ginn had his electronics business. Aside from that, The Church was filled with a bunch of hippie merchants making pukka shell necklaces or stained glass, and selling drugs on the side. It became kind of a center for some of Black Flag's fans and groupies and hangers on.

Al Barile: I met Chuck Dukowski the first time I saw Black Flag, in 1980. They were playing Ralph's Diner in Wooster. He was playing bass, and he had that nice shiny head, and it was really enticing, so I thought I had to give him a head butt. And when you give someone a head butt there has to be this unspoken communication between each other, like, "Okay, our heads are gonna meet.' I saw stars. He did too. I think we might have proceeded to give each other one more head butt. I think it was probably, like, a two head butt night.

Andy Wendler: Barry Hensler and I started the Necros when we had both just turned sixteen, in 1979. We got our name from this pulp fiction book from the fifties called The Necrophiles. We just thought it was a great, classic name: like Ramones, Beatles, Necros. And no, it wasn't because somebody in the band had fucked a corpse.

Lyle Preslar: Our popularity began to spread through singles we sold while we were on the road. After a tour, we'd pick up some fanzine from Alaska with a Minor Threat rave review. I think a lot of the DC locals resented it, so we did a song called "Cashing In," and we threw money at the crowd.

Gregg Turner: At first, we thought up real terrible names for the band, like the Mind Parasites, or the Frozen. But I used to write for this little fanzine in Carson, which is an industrial suburb that has a big Samoan population. One night I'm out there late, like eleven p.m., and I get out to my car and there's all these big Samoans wandering around in arbitrary paths of orbit. It looked like a George Romero casting call for strange big ethnic people, and two of them were sitting on the hood of my car. We're talking maybe a total of 600 pounds. So I bought three six-packs of Rainier beer and gave it to them. We became soulmates, and they gave me their phone number just in case I needed anybody's ass kicked. They weren't angry Samoans at all, but that's where we got the name.

Al Barile: SS Decontrol was the first real Boston hardcore band and the whole Boston hardcore scene actually started in art gallerys. The owner of one of these gallerys had this arty band that I hated playing there, and I went to the show and I put my hand through the wall of his art gallery. I was kind of a nice guy and I felt bad that I put my hand through this wall that he used to hang paintings on. So I told him that I would come back the next week and fix it. He said, "Oh yeah, sure.' But I did come back to fix it, and then I said, "I got this band, and I'd really like to play here....'

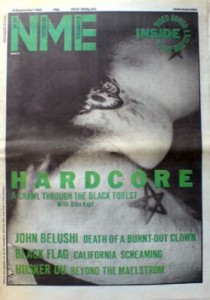

Gregg Turner: One of the last great things John Belushi contributed to the world was getting Fear to play Saturday Night Live. It seemed highly improbable and sort of astounding. Even back in the early eighties, there was a buzz about hardcore punk but it was still a pretty under-the-carpet sort of thing. SNL was the real clarion call. When I saw something like that on tv and thought about what kind of an invasion it was to the consciousness of millions of people who'd never seen punk before, I started thinking that this music could explode.

Henry Rollins: The first State Of Alert show lasted about 12 minutes. Our songs were thirty seconds long. It was primitive thrash punk with a broken drum set. Before the first song started, I was so nervous I punched my friend Jay right in the head. In those days we were used to getting hit a lot.

Gregg Turner: To get the Angry Samoans together, we put ads in the Recycler, which is this LA classified ad hand-out. We would call people back and ask them "What are your influences?', and if they said things that were palatable like the Ramones, we'd say "Okay, you're in.' If they said the Allman Brothers, we'd say "Alright, talk to you later.'

Al Barile: I was brought up in the typical suburban thing where you get beer on the weekend and you drink. The people who didn't drink were always the sissies. But when I met Henry Rollins and this whole group of DC people, I said, "Hey, this is interesting, these people are definitely not sissies, and they're saying screw it, we don't need to drink.' That was how I found the strength to say no. And I was proud of that. I don't think I ever made the decision to drink--I felt that decision was made for me somehow. But Straight-edge meant the choice was mine--no one made it for me. Minor Threat had the song "Straight Edge', but in Boston we kind of marketed straight-edge. There were even myths that we'd knock people's beers out of their hands. That might have happened once or twice. There were straight-edge chants that people would do before our shows.

Henry Rollins: The first time I realized I could intimidate people was onstage. With Black Flag. After the first tour I did with them, the word was out: that new singer in Black Flag-very intense. That was the key word-"Intense.' But I was always very good at being abusive. That's what I grew up with.

Al Barile: I met Henry Rollins once before he became indoctrinated into the Black Flag style of life. If you look at the Henry period of Black Flag, you can see that at first he was a skinhead, this DC kid, and then he went into this Jim Morrison phase. Henry was cool on his own, but Black Flag transformed Henry into this LA Henry. And the Henry band wasn't the Black Flag that kinda drew me in. He was into this trip, ya know? I think he became an ego maniac.

Gregg Turner: When we recorded Back from Samoa, everything just sounded thrashy and loud and we just thought it was a joke and we didn't have anything to lose. After the record came out, in 1984 or so, this guy from Boston phoned us up and said "Hey, I want you to headline this club called The Channel.' He said he'd put us up at a Sheraton and he sent me plane tickets, and we thought this guy was on drugs or something. We got to Boston and there were about 25,000 kids who knew every syllable of every word of every song. In fact, when we played ""Lights Out,'' a hundred and fifty kids in the front just erupted and pulled out these little white plastic forks and started doing mock eyeball impalements.

Darryl Jennifer: [Bad Brains singer] HR would start a show by jumping from a balcony. Once in 1983 or so, he made us duct tape him to a chair at the beginning of a gig, and then he tore his way out of it in the first five minutes. Bad Brains was like spiritual exorcism. The instruments coulda' played themselves.

Henry Rollins: Black Flag was a lot of hungry times, a lot of missed meals. Sleeping in your wet clothes in the back of the van. Imagine living in Das Boat for five years. We did a demo once while we were out touring. I dug it out the other night and I had just forgotten how powerful we were. Everytime we played, it was like dogs on a leash trying to break the chain, like a hungry man going towards food. This tape sounds like Vietnam warmed over. It's the kind of music you make when you're really poor and lean. That band started on ten. The tape was just done in one night, one take, mixed, the sun came up and we were out of there. It never came out--it was just a good night.

Andy Wendler: I remember looking at an issue of Thrasher magazine in 1983 and almost every skater that was doing any sort of lip maneuver had a Necros sticker on his board.

Sammy, Youth of Today, CIV: We would do fanzine interviews, but some of the kids would lie and make up names of fanzines they wrote for, just so they can hang out with us.

Mike Muir, Suicidal Tendencies: We were playing these shows with thousands and thousands of people, and some punks thought that was "selling out.'' Once this kid at a show told me we should go back to playing places that only held two hundred people. And I said, `Well, you must be using some sort of new math.' The hypocrisy in punk rock was amazing.

Raymond Pettibon: There was a lot of violence sometimes at these gigs. If some unfortunate hippie type would wander in, you could be sure that he wouldn't walk out without being bloodied. But there were also riots at punk shows that were obviously planned beforehand by the police, probably as tactical training for future race riots. They'd come in full riot gear, with dozens of cars, whole squads of cops, sixty or seventy of them, and just brutalize anyone they could. Their main targets were the most defenseless people, like thirteen-year-old girls. There was this one show at a rented hall out in the City Of Industry, and we showed up after the riot had already happened. There was glass all over the place. This comical five-foot-two cop comes up to us on his tippy-toes, like he was in a Charlie Chaplin movie, in that silent film speed, and he gives me a whack on the shoulder with his nightstick. He swung like the sissy kid in grade school, but you know those nightsticks are filled with lead. I was with these two girls, and the cops beat up the girls really viciously. It was the sickest thing in the world to see the violence in their eyes. I think if I would have tried to help my friends, I would have been beaten to death or shot.

Al Barile: My wife used to manage the Sadistic Exploits in Philly, and she booked the infamous SS Decontrol/Minor Threat show in Camden where [Minor Threat singer] Ian MacKaye almost got killed. The show was at this Knights of Columbus hall or a VFW hall in the worst black neighborhood you could ask for. We pulled up in our van, and Ian came across the street into my lane to talk to me. All the sudden this car comes flying down the street, bearing down on us, coming sixty miles-an-hour at us. He was gonna hit Ian. So he hits us head-on, and Ian jumps up the side of the van. The other guy smashed into my van but deflected off of us so that there was enough space between us for Ian to survive. He escaped unhurt. But it was close enough to hit Ian's sneaker and knock it flying. When we got out of the van, Ian was saying "They hit my shoe.'

Raymond Pettibon: I remember once when I was getting ready to go to a show, around 1982, and someone asked me where I was going, I told them `I'm going to a riot.' I just said it matter-of-factly, because I knew that's what I was doing. And there was a riot that night.

Andy Wendler: I remember being at some Detroit shows with punks chasing people outside, and kicking them. I even remember some people chasing a guy outside a club and killing him. I didn't know the people who did that, but I, uh, I knew of them. It was really, really disheartening, just a major bummer for everybody involved.

Al Barile: Actually, the people I got the most hostility about straight edge from was Rollins and Black Flag. They had probably been drinking and drugging the whole time. I lost a lot of friends because they continued on that path of drinking. Somewhere in the eighties some people from Madison entered the Boston scene, and they brought a drug thing with them. And I kind of lost my crew to that.

Andy Wendler: In Detroit, there was Bored Youth and Youth Patrol. There were so many "youth' bands. Reagan Youth. Wasted Youth. Youth of Today. I think there was even a Youth of Tomorrow at one point. Probably worse than all the Youths was all the Crosses. Every city had five White Crosses, and Red Crosses, Iron Crosses, Black Crosses--that just got a little outta control. There was the Stain or the Stains in every town. There was a Toxic Shock in every town. I never figured out why there wasn't a band called Tylenol Scare. I kept cringing, just waiting for that to happen.

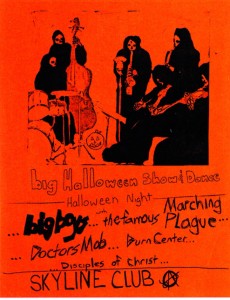

Tim Kerr, Big Boys: There was a circuit of racist skinheads moving from Chicago to San Francisco to Austin to Dallas.

Darryl Jennifer: We had to deal with racism, but it wasn't a big deal. A German kid threw a beer on me once, so I dropped him. At the Cat's Cradle in Chapel Hill, the owner threatened us once--he said he wasn't gonna pay us, and that if we didn't like it, he'd get all his machine guns and biker friends and dogs after us. A lot of these skinheads weren't real Nazis, they were just frontin.' Racism doesn't exist if you don't let it. These days, Nebraska skinheads don't hate blacks anymore--they just hate the next town over.

Henry Rollins: A lot of those skinheads didn't realize how pansy-assed they were. A few years ago in Long Beach, some skinhead smacked this young Samoan kid. The kid went and told his big brother and a bunch of these Samoans took the skinhead to the back of the parking lot and just shot him. Took part of his head off. That's what happened to some of the skinheads: they just upped the ante until someone really cleaned their clock.

Darryl Jennifer: In about `84 or `85, the shit crossed over to being this no-assed metal hardcore. And I know HR got disillusioned with all the blood and violence.

Andy Wendler: Hardcore had become a prison. It became formulaic and very limiting. By the summer of 1985 or "86, it had just become something that everybody's little brother got into for one summer before their senior year. We took a lot of flak because we went on tour with Megadeth. Kids at shows were like, "Why are you trying to be a third rate metal band?' They felt like we were letting down "the scene.' Which is ironic because three summers later, hardcore and speed metal were basically the same thing.

Henry Rollins: Black Flag ended on pretty bad terms. Greg called me and said, "Uh, I quit.' Seeing as how it was Greg's band, I just said, "Cool, man, whatever.' There was no big comaraderie in Flag. The day Greg called me to quit I didn't know him any better than I did five years before when I saw Black Flag from the audience.

Al Barile: I used to get calls from sixteen-year-olds saying "Straight-edge is this and that', and I felt I had affected someone's life in a positive direction. I felt damn good about that. I never felt like hardcore was gonna change people's lives. But I did think that maybe people could go through the experience I had gone through and then going around and getting fucked up would not become a priority in their life. That's the only idealistic hope I had about it.

Raymond Pettibon: It's disconcerting because punks were always against the boring old farts and the idea of hanging around past your best days. And now, not only are the Rolling Stones bigger than ever, but the Adolescents are bigger than ever.

Sammy: In Youth of Today, we used to play in pizza parlors. Ten years later, when I was singing for CIV, we would play festivals in Florida for twenty thousand people.

Al Barile: To be honest, the one thing I could say about Green Day is that I despise that English accent thing. I could never like them because of that alone, ya know?

Sammy: I'm, uh, not really interested in the Circle Jerks reunion record.

Lyle Preslar: Hardcore was a burn-out thing, and I'm not that person anymore.

Mike Muir: Suicidal Tendencies' message was that sometimes you fight with your fists, and sometimes you fight with your mind. You should make it known that you won't be a victim. I believe in empowerment. I don't believe in horoscopes. Life should be the long process of learning to control your own destiny.

Raymond Pettibon: A lot of the people involved in hardcore were really serious. Like this was a life changing matter. Their haircuts were world-historical issues. They were kind of innocent about it. These weren't wizened people yet. They didn't see it as a stage of life that they were passing through. These fourteen-year-old runaways would ask me whether they should drop out of school and hit the scene. I would always tell them, "If you don't get your high school diploma now, that can affect the rest of our life. Whereas this music will probably be played out within five years.' There's a lot of casualties from punk, people who bought into it. It destroyed a lot of people. Crashed ideals, lost opportunities to grow. The whole slacker movement or mentality that came later seemed to me to have something to do with the opportunities that punk wasted.

Stephen Malkmus, Pavement: I was in a hardcore band. It was better than being on the football team. I pretended that I liked [Black Flag's album] Damaged. I couldn't really understand the Minutemen. MDC was hot around the neighborhood, so we had to put up with that. Hardcore punk rock was just part of your upbringing: SST in it's golden era, the Homestead records--you know, classic rock.